The collection of American Art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in Manhattan is one of the finest and the most comprehensive in the world. It was recently updated and provides visitors with a rich and captivating experience of the history of American art from the eighteenth through the early twentieth century. The suite of elegant new galleries encompasses 30,000 square feet for the display of the Museum's superb collection.

At first, I was suddenly aware of the level of craftsmanship for the period the artifacts were from, where machine aid was not available.

Then I started to notice objects that were made with more than one material. For example, here's a Tea urn and Tray by John McMullin (1765 ~ 1843), made in Philadelphia, 1799.

It is mainly made of Silver, but the part where it would be touch the most is made with ivory.

Here is William Will's (1742 ~ 1798) Teapots made in Philadelphia between 1764 ~ 1798. It's pewter but notice the wooden handle. Here he must have considered the teapots would have been too hot to touch and therefore a wooden handle would insulate the heat from the user. It also provides a nice color contrast. The design is consistent with the rest of the pot.

Here's a goblet made in 1791 by the New Bremen Glass Manufactory (1784~1795) of John Frederick Amelung (active 1784 ~ ca 1791). Blown and engraved glass with wood.

I'm not sure about the true intention of the wooden base but aesthetically it seems give the goblet a more sturdy look.

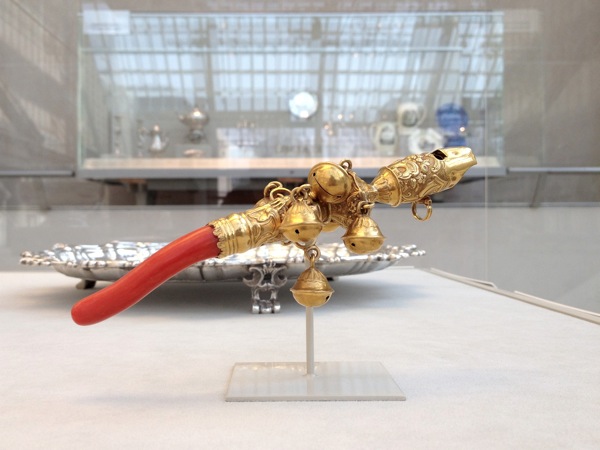

Here's something I have never seen before. "Rattle, whistle, and bells" by Nicholas Roosevelt (1715 ~ 1769), made of Gold and Coral. It is a rare and lavish gold toy, with its elaborate chased and repoussé ornament, which may have been presented as a christening gift. It consists of a whistle, a piece of coral, size of its original eight bells, and a loop that allowed it to be hung from a ribbon around a child's neck. Aside from its efficacy for teething, the coral was thought to ward off evil spirits and disease. New York City, 1755 ~ 1768.

Here is another sample by Peter or Richard Van Dyke of New York City, between 1735 ~ 1745. It is made of silver and coral.

The use of coral in this instance is very interesting in that it has mechanical properties that could withstand a child chewing on it, but also its intension to ward off evil spirits and disease, which also speaks to the state of medical sciences at the time.

In the realm of furniture making in the same period, wood was the predominant material of choice, which is not surprising. Of course wood is still the predominant material now. The pieces on show demonstrated a level of aesthetics that is no longer sort after by the masses. Here are a set of examples featuring "Japanning" - the use of paint and gilded gesso to imitate the glossy finish on Asian lacquerwork. It was a popular method of furniture decoration in colonial Boston. This group os japanned furniture descended in the Pickman family of Salem, Massachusetts, and is an extraordinary survival. The painted decoration on the high chest, dressing table, and looking glass is all by the same hand. Boston, 1730 ~ 1760.

High chest drawers are made from maple, birch, white pine.

Dressing table, maple, birch, white pine. Looking glass, white pine.

It seems jewelry makers were making much more progress in combining materials, perhaps driven by the need to make objects that look apart. The scale of each piece was probably also a factor. Here is an urn made by William E. Brigham (1885 ~ 1962) of Providence, Rhode Island, ca 1927. It consists of amethyst silver, tourmaline and other semi-precious stones. This urn was exhibited at the Tricennial Exhibition of The Society of Arts & Crafts in Boston in 1927.

Made in New York City in 1893 by Tiffany & Co (1837 ~ Present), this cup is made from amboyna wood, silver, mother of pearl and turquoise. Described in Tiffany's records as a "love cup," it was designed for display at the Word's Columbian Exposition. THe shape references Viking objects, while the ornament draws on a variety of foreign and domestic design sources.

At the same Columbian Exposition, Tiffany & Co also displayed this Viking Punch Bowl designed by Paulding Farnham (1859 ~ 1927). It is made with iron, silver, gold and wood.

The Viking Punch Bowl was one of the most celebrated and publicized works exhibited by Tiffany & Co. At the World's Columbian Exposition. Conceived as a commemoration of European explorations of North American prior to Columbus's voyage, the bowl's design and ornament refer to Norse peoples and their culture. According to the firm's catalogue for the exhibition, the handle terminals projecting through the bowl's rim were "suggested by the prow of the Norseman's boat."

Tiffany & Co also presented a cup and saucer from 1890 that was made with a combination of metals: silver, copper and niello, which is a black compound of sulfur with silver, lead, or copper, used for filling in engraved designs in silver or other metals.

Also from Tiffany & Co, a Mustard Pot from1883 made from Silver and marbleized alloys.

Areas of gold-and-coper mokume envelop the body of this covered mustard pot on four bracket feet. A mixed-metal laminate that takes its name from the Japanese word for "wood grain" (literally, "wood eye"), mokume. Here, the wavy panels of mokume are bordered by etched scrolls and flowers.

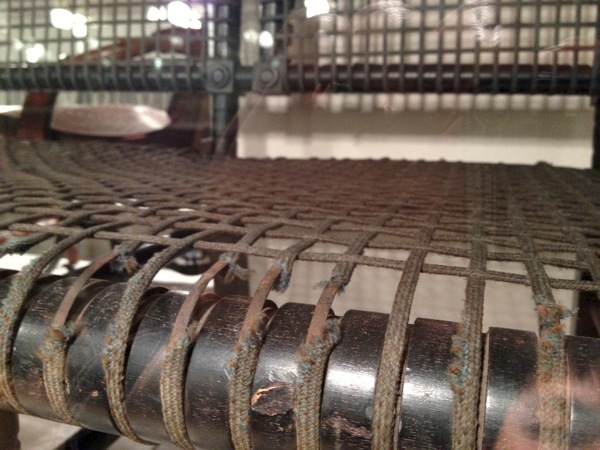

Wondering into the archives, I found an armchair (1876) and a settee (1876 ~ 1885) by George Jakob Hunzinger (1835 ~ 1898) who combined maple or ebonized cherry with fabric-covered steel mesh for the seating surface.

There was also a special exhibit on Duncan Phyfe's furniture. He was one of nineteenth-century America's leading furniture makers. Born near Loch Fannich, Scotland, he emigrated to Albany, New York at age 16 and served as a cabinetmaker's apprentice. In 1792, he changed the spelling of his surname (Fife to Phyfe), moved to New York City, and opened his own business in 1794, which eventually employed more than 100 workers. He became known as one of America's leading cabinetmakers by selling furniture at relatively low prices. Although Phyfe's work encompassed a broad range of the period's classical styles -- Empire, Sheraton, Regency, Federal and French Classical among them -- he was most famous for his simple style, a reaction to the imported French designs popular at the time. Duncan Phyfe's furniture can be seen in the White House Green Room, Edgewater, Roper House and Milford Plantation owned by the Classical American Homes Preservation Trust, museums, etc.

This Secrétaire à abattant was attributed to Duncan Phyfe and was made by his factory between the years of 1835 to 1847. It is made of Mahogany, mahogany veneer, gilded brass, looking-glass plate, marble, ivory; secondary woods of white pine, yellow poplar and mahogany. It is simple, yet refined, a tour-de-force example of the Phyfe shop's renowned use of spectacularly figured mahogany veneers.

The marble top was the element that really caught my eye as I came down those stairs. Since it's a museum piece and not to be touched, I can only speculate that in addition to the aesthetics, the marble added to the sturdiness of the piece as it is above what would be considered as a height for a table or resting surface.

This sideboard, made between 1840 ~ 1847, is a prime example of D. Phyfe & Son's late Grecian Plain style, updated by the silhouetted Gothic cusps and ogees cut into the arched heads of the plate-glass doors and the fascia over the open center bay. The catalogue to the 1847 auction of the contents of the D. Phyfe & Son warerooms lists a sideboard that could well refer to this one: "1 splendid rosewood Sideboard, with marble top and back, gothic door and plate glass panels, mirror back, lined with white silk."