While the modern game of golf originated in 15th century Scotland, the game's ancient origins are unclear and much debated. Some historians trace the sport back to the Roman game of paganica, in which participants used a bent stick to hit a stuffed leather ball. One theory asserts that paganica spread throughout Europe as the Romans conquered most of the continent, during the first century BC, and eventually evolved into the modern game. Others cite chuiwan ("chui" means striking and "wan" means small ball) as the progenitor, a Chinese game played between the eighth and 14th centuries. A Ming Dynasty scroll dating back to 1368 entitled "The Autumn Banquet" shows a member of the Chinese Imperial court swinging what appears to be a golf club at a small ball with the aim of sinking it into a hole. The game is thought to have been introduced into Europe during the Middle Ages. Another early game that resembled modern golf was known as cambuca in England and chambot in France. This game was, in turn, exported to the Low Countries, Germany, and England (where it was called pall-mall, pronounced “pell mell”). Some observers, however, believe that golf descended from the Persian game, chaugán. In addition, kolven (a game involving a ball and curved bats) was played annually in Loenen, Netherlands, beginning in 1297, to commemorate the capture of the assassin of Floris V, a year earlier.

Golf was played in its present form in Scotland near St. Andrews in the 1400s. Players used primitive equipment made of tree limbs and shepherd’s crooks that were fashioned with club-like bottoms to play the game in rather haphazard and casual manner. Players used one club for all their shots and hit round rocks or pebbles, they soon turned to skilled craftsmen to produce competitive equipment.

There is one documented reference of a John Daly playing with a wooden ball in 1550.

Golfers became so obsessed with the game that they forgot archery practice and thus banned by the King of Scotland, James IV, in 1458, 1471 and 1491. In 1502, the first recorded purchases of golf equipment, a set of golf clubs costing thirteen shillings, was made by king James IV from a bow-maker in perth.

The first clubs made specifically for golf were probably made by bow makers who were familiar with the whip-like properties of wood. Carved wooden heads from beech, holly, dogwood, pear or apple and spliced into the shafts of ash or hazel. Improvements were made by filing the back of the head with lead and by putting inserts of leather, horn or bone into the club face.

There is an authentic record of a club maker in 1603 where William Mayne was appointed to the court of James I of England (aka James VI of Scotland) to make clubs for the king and his friends. A set of clubs at the time consisted of a set of play clubs (longnoses) for driving, fairway clubs (or grassed drivers) for medium range shots, spoons for short range shots, niblicks (similar to today’s wedges) and a putting cleek. The clubs especially long-noses and niblicks were also prone to breakage and a golfer could expect to break at least one club during a round. The cost, time and effort which went into making golf clubs priced them beyond the reach of the masses. These factors meant that golf was typically associated with the upper echelons of society. Andrew Dickson of Leith and Henry Mill of St Andrews were recognized as club makers in Scotland in the late 1600s.

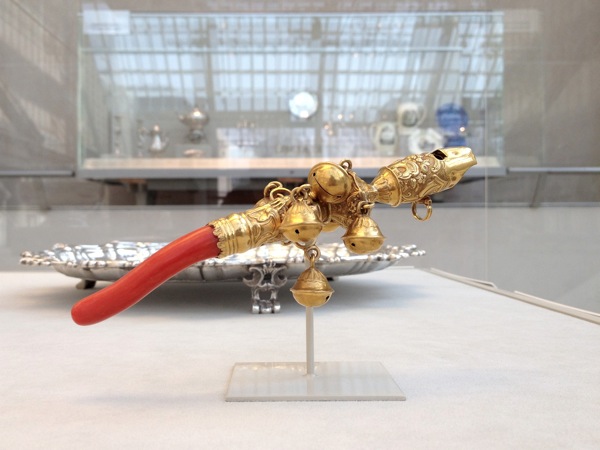

Featherie, 17th century, bull or horsehide leather encased sphere stuffed with feathers from goose down or chicken feathers. Takes a long time to make. Stuff the wet, leather casing with a top-hat-full of down feathers that had been boiled. The casing is then sow it up, and let it dry so the feathers would expand while the leather would shrink into a rather hard ball.

If there were openings in the leather, stitching was used to close them up. The stitches mimicked the effects of dimples, therefore the need for a layer of turbulence around the ball was not discovered until much later. When playing in wet weather, the stitches in the ball would rot, and the ball could split open after hitting a hard surface.

Each ball was expensive, 2 shillings and six pence and 5 shillings. (Equivalent of $US 10 to 20 today). It was also fragile so the cost was inaccessible to many people. Great variance between balls. Weight, sizes. Does not stay a sphere for long after being struck a couple of times. At most 3 featherie per day.

In 1618, James I of England comissioned James Melvill and an associate to make feathery balls for court. It was an exclusive grant for 21 years with the balls stamped by Melvill and any other ball found in the Kingdom not bearing his trademark were confiscated. In dry weather, the feather ball could travel 180 yards, 150 in wet conditions.

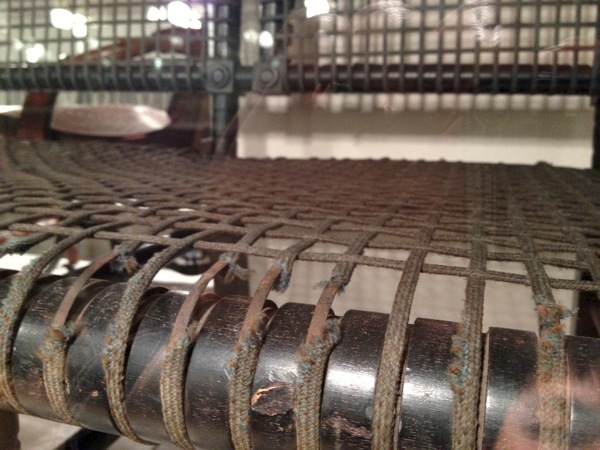

In the 18th century, a club maker fashioned a block of blackthorn wood into a banana-shaped head and joined the head with a long shaft of ash or hazel that would have a splice in the wood called a “scare.” The two were wrapped, secured together with fisherman’s twine. Grips were made from sheepskin or calfskin.

At some point in time it was decided that the first shot of each hole could be teed up. Tee was originally meant and is still used to refer to the teeing ground but it has also become synonymous with the implement used to elevate the ball. Initially players would take a pinch of sand from the bottom of the cup as they too their ball out. They would then use that sand to tee up their ball for their next shot. By the 18th century bags of sand were carried by players for teeing purposes and eventually trays or boxes of sand were placed around the teeing area.

In 1744, the first standardized rules of golf were written and used for the first golf championship, won by Dr John Rattray on April 2nd, 1744.

A variety of clubs had emerged with slight variations. “Play Club” to tee off. “Lofted Spoons” to hit the ball off the ground. “A Baffing Spoon” or “Baffy” to hit a pitch-like shot. The only irons before the invention of the gutty ball were rut iron or “rutter” used to scoop the ball out of wheel ruts and a comblike track iron used to hit the ball out of stones. As early as 1750 some club-makers used forged metal heads of niblicks.

When golf was introduced in America in the early 1800s, hickory wood began to be used in shafts, due to it’s availability. Hickory became so popular for shafts that in 1826, a club-maker, Robert Forgan of Scotland, began to use hickory imported from America to manufacture shafts in Scotland. The hickory shafts required a slow, smooth swing to correctly time the hitting of the ball. They were also prone to breakage. Yet golfers adapted to the available technology and the game moved on.

Early “irons” were made by local blacksmiths until around the late 1800s. As a result they were very crude and heavy with massive hosels and were very difficult to use. That and the fact that they easily damaged the featheries led to their limited use.

Gutty, 1848. Reverend Adam Paterson, a clergyman from St. Andrews, made the gutty ball by hammering coagulated strips of gutta-percha tree resin, from south east Asia, into a mold. Paterson had received the gutta-percha as padding that covered a gift. He found the material could be softened with heat and then molded into a hard ball. Led to higher production, lowering costs. 6 dozen gutties per day. Smooth balls would travel erratically like a whiffle ball... but scuffed up balls travelled further and straighter so they started adding raised bumps, called bramble patterns, to increase aerodynamics. 225 yards.

Gutty, 1848. Reverend Adam Paterson, a clergyman from St. Andrews, made the gutty ball by hammering coagulated strips of gutta-percha tree resin, from south east Asia, into a mold. Paterson had received the gutta-percha as padding that covered a gift. He found the material could be softened with heat and then molded into a hard ball. Led to higher production, lowering costs. 6 dozen gutties per day. Smooth balls would travel erratically like a whiffle ball... but scuffed up balls travelled further and straighter so they started adding raised bumps, called bramble patterns, to increase aerodynamics. 225 yards.

Some sources cite the guttie ball being made with Malaysian Sapodilla tree which is in the same family as the Gutta-Percha.

It could also be easily repaired by re-heating and then re-shaping.

The guttie ball quickly rendered longnoses obsolete. Bulgers, closely resembling today’s woods in that they have a bulbous head, were used to cope with increased stresses incurred by using the new ball.

The gutta-percha ball enormously enhanced the game of golf, however it was soon discovered by golfers who failed to smooth their balls by boiling and rolling them on a "smoothing board" after play, that a many "nicked" ball had truer flight than the smooth gutta. Thus the hand hammered gutta was created by hammering the softened ball with a sharp edged hammer ... giving the ball an even pattern that greatly improved its play. Later, balls formed in iron molds or ball presses that created patterns or markings on the ball were introduced. A wide variety of surface patterns were introduced into golf.

The Bramble, surface textures and patterns impressed into the gutta-percha balls evolved from early imitations of feathery ball stitching to the highly detailed and symmetrical that greatly improved the ball’s flight. The best known balls were the hand-marked private brands of the Scottish club makers, such as Morris, Robertson, Gourlay, and the Auchterlonies. Many brands with a variety of patent names used the bramble pattern (with a surface similar to the berry). This became the most popular pattern of the gutta era and was also used on some of the early rubber balls.

Many of the rubber companies including Dunlop began mass-producing balls which killed off the handcrafted ball business.

Gutty balls could withstand the blow from iron clubs so metalworkers began to craft iron-headed clubs. These new club-makers in the history of golf equipment were known as cleekmakers.

These new irons were: the cleek, used to tee off and was like a two iron. The mashie, used for fairway shots and was like a 5 iron. The niblick, which was used for pitch shots and was like a nine iron.

The gutty ball also changed spoon and play clubs. Club heads became shorter and wider to prevent damage to the wooden face of the club head. They also started placing inserts made of leather into the club face for some reason. Splicing of the head and shaft together was abandoned in favor of placing the end of the shaft in a hole in the club head.

In the 1880s, golf bags first come into use. “The beast of burden” is an old name for the caddie who carried golfers’ equipment for them.

In 1889, the first documented portable golf tee was patented by Scottish golfers William Bloxsom and Arthur Douglas. This golf tee was made from rubber and had three vertical rubber prongs that held the ball in place. However, it layed on the ground and did not piece (or pegged) the ground like modern golf tees.

A British patent was granted to Percy Ellis in 1892 for his “Perfectum” tee that did peg the ground. It was a rubber tea with a metal spike.

In 1895, David Dalziel of Scotland patented a rubber tee that was combined with artificial-turf mat in the US.

American Proper Senat received a patent for his tee in 1895. It was a truncated cone made of paper or cardboard.

Scotsmen PM Matthews patented the “Vicktor” tee in 1897, similar to the Perfectum but included a cup-saped top to better hold the golf ball.

Haskell Ball, 1898. Invented by Americans, Coburn Haskell (Dentist) and Bertram Work of the B. F. Goodrich Company.

This idea was first discovered by Coburn Haskell of Cleveland, Ohio in 1898. Haskell had driven to nearby Akron to keep a golf date with Bertram Work, then superintendent of B.F. Goodrich. While he waited for Work at the plant, Haskell idly wound a long rubber thread into a ball. When he bounced the ball, it flew almost to the ceiling. Work suggested Haskell put a cover on the creation, and that was the birth of the 20th century golf ball.

Constructed by tightly wrapping rubber bands under tension around a rubber core and holding the inside together with the Balata cover. This ball took off like a rocket, soaring through the air. Detractors of the ball would call it the “Bounding Billy” because the ball would dart off the ground upon landing. 430 yards.

The advent of drop forging in the late 1800s meant better iron clubs could be massed produced in factories.

By the end of the 19th century, golfers began to develop individual, portable gadgets to prop the ball up. In 1899 George F. Grant, a Boston dentist, patented a wooden golf tee that is similar to the ones commonly used now. It was a wooden spike with a tubular rubber head.

Through experimentation the cores of the balls become bigger and the cover thinner, which provided “truer” ball flight. In 1900 John Gammeter invented an automated winding machine that allowed mass production of Haskell golf balls.

Universally adopted by 1901 the Haskell ball proved so effective in the British and US Opens, these balls looked just like Gutties but gave the average golfer an extra 20 yards from the tee.

A popular alternative was aluminum in keeping with tradition of hand-forging metal club heads. In 1902 E. Burr introduced groove-faced irons for increased backspin, which lead to more distance and control.

In 1905 (1908?), golf ball manufacturer William Taylor was the first to add the dimple pattern using the Haskell ball.

Manufacturers continued to experiment with golf ball design including Goodrich who introduced the pneumatic ball in 1906 (the patent was held by T. Saunders and filed in 1901). Quite simply this was a Haskell ball with a compressed air core which unfortunately was prone to expansion with heat and therefore causing the ball to explode. Others tried mercury, cork and metal cores.

Wooden headed clubs were usually hand made by the local professionals until perhaps 1910, when factories began to take over due to the demand.

With the introduction of the Haskell ball, wooden club heads started being made with persimmon wood. In the 1920s, equipment companies began making clubs with steel shafts, which gave clubs uniform strength and feel. The USGA authorized the use of steel-shafted clubs in competition in 1926. The R&A followed in 1929.

William Lowell, patented a wooden peg with concave, funnel-shaped head in 1922.

In 1931, the USGA declared a ball should weigh no more than 1.55 ounces and no less than 1.68 inches in diameter. Now R&A (Royal and Ancient Golf Club of St Andrews, ruling authority for golf in Europe) and USGA have come to an agreement that balls should weigh no more than 1.62 ounces and no less than 1.68 inches in diameter.

Gene Sarazen, American Golfer, wanted a club that would not dig into the sand when he was in the bunker so he soldered a flange onto the bottom of his niblick, inventing the sand wedge in 1932.

Golfers carried as many clubs as they deemed necessary until 1938 when the rules of golf were changed to restrict the number of clubs to fourteen.

Since the end of World War II, golf club development has been influenced by research into synthetic and composite materials.

In the 1960s, Karsten Solheim, a Norwegian-born American golf club designer, founder of the Karsten Manufacting Company and creator of Ping golf clubs invented “perimeter weighting” where the mass of the club was distributed around the perimeter of the club, thereby increasing the club’s sweet spot, making it much more forgiving. Solheim also used a new manufacturing process called investment casting where molten metal is poured into molds to form the shape of the club head allowing the weight to be moved to the edges and creating cavities in the club head.

First powered golf cart appeared around 1962, invented by Merlin L. Halvorson.

The first graphite shaft was introduced in 1973. Early graphite shafts, although lightweight and theoretically stronger, were inconsistent and prone to too much torque or twisting. Since then, manufacturing procedures have made those problems pretty much a thing of the past. Boron is used to reduce twisting.

Gary Adams, founder of TaylorMade, developed and began producing woods made of metal in 1970. In the 1990s, companies began experimenting new materials such as titanium, which allowed club heads to become bigger and lighter, increasing forgiveness and performance. Their thin faces increase the spring like effect of the ball off the club face and theoretically can increase distance.

The Haskell Ball technology dominated the world of golf for a century. Better players played continued to play with three-layered balls but less-skilled players switched to a two layer ball with a solid rubber core and durable Surlyn cover. The solid core balls flew further but could not generate the same spin better players were looking for.

In 2000, companies started manufacturing three layer balls with solid cores and a softer urethane or surlyn cover. Ball technology continues to evolve with four and even five layer balls being produced now.

Most golf balls on sale today have about 250 – 450 dimples, though there have been balls with more than 500 dimples. The record holder was a ball with 1,070 dimples — 414 larger ones (in four different sizes) and 656 pinhead-sized ones. One odd-numbered ball on the market is a ball with 333 dimples, called the Srixon AD333.

Officially sanctioned balls are designed to be assymmetrical as possible. This symmetry is the result of a dispute that stemmed from the Polara, a ball sold in the late 1970s that had six rows of normal dimples on its equator but very shallow dimples elsewhere. This asymmetrical design helped the ball self-adjust its spin-axis during the flight. The USGA refused to sanction it for tournament play and, in 1981, changed the rules to ban aerodynamic asymmetrical balls. Polara's producer sued the USGA and the association paid US$1.375 million in a 1985 out-of-court settlement. Polara Golf now manufactures balls with “Self-Correcting Technology” for non-tournament play.

The United States Patent and Trademark Office's patent database is a good source of past dimple designs. Most designs are based on Platonic solids such as icosahedron.

Golf balls are usually white, but are available in other high visibility colors, which helps with finding the ball when lost or when playing in low-light or frosty conditions.

As well as bearing the maker's name or logo, balls are usually printed with numbers or other symbols to help players identify their ball.

More recently RFID transponders have been used for this purpose. This technology can be found in some computerized driving ranges. In this format, each ball used at the range has its own unique transponder code. When dispensed, the range registers each dispensed ball to the player, who then hits them towards targets in the range. When the player hits a ball into a target, they receive distance and accuracy information calculated by the computer.

Hybrid clubs offer the marriage of wood and iron technology and this new category ahas also offered major game improvement and forgiveness options in the long iron area. It is popular with beginners and slow swingers.

Graphite shafts not only increased swing speed but also flex characteristics.

Club technology continues to advance with the governing bodies doing their best to stave off the innovations from making skill less and less important. The USGA has limited the size of driver heads to 460 cubic centimeters and the new 2010 groove rule are just some of the steps they have taken.

Rangefinders, GPS and other handheld devices let golfers view the entire hole, exact distances to many different points and keep score.

Bibliography

http://www.laymansgolf.com/golf_articles/history_of_golf/history_of_golf_equipment/8/

http://www.tourcanada.com/golfhist.htm

http://inventors.about.com/od/gstartinventions/a/golf.htm

http://www.golf-club-revue.com/golf-club-history.html

http://www.thedesignshop.com/history.htm

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Golf_ball

http://www.kingjamesvi.co.uk/history.cfm

http://www.golfeurope.com/almanac/history/golf_club1.htm

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tee

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Golf

Gutty, 1848. Reverend Adam Paterson, a clergyman from St. Andrews, made the gutty ball by hammering coagulated strips of gutta-percha tree resin, from south east Asia, into a mold. Paterson had received the gutta-percha as padding that covered a gift. He found the material could be softened with heat and then molded into a hard ball. Led to higher production, lowering costs. 6 dozen gutties per day. Smooth balls would travel erratically like a whiffle ball... but scuffed up balls travelled further and straighter so they started adding raised bumps, called bramble patterns, to increase aerodynamics. 225 yards.

Gutty, 1848. Reverend Adam Paterson, a clergyman from St. Andrews, made the gutty ball by hammering coagulated strips of gutta-percha tree resin, from south east Asia, into a mold. Paterson had received the gutta-percha as padding that covered a gift. He found the material could be softened with heat and then molded into a hard ball. Led to higher production, lowering costs. 6 dozen gutties per day. Smooth balls would travel erratically like a whiffle ball... but scuffed up balls travelled further and straighter so they started adding raised bumps, called bramble patterns, to increase aerodynamics. 225 yards.